This is a mirror of my post in Medium.

Figure: How the transition from acadmy to industry looks like. Combined from Unsplash images. (This one and this one.) Here and in what follows the term ‘industry’ simply refers to any non-academical company or position.

Figure: How the transition from acadmy to industry looks like. Combined from Unsplash images. (This one and this one.) Here and in what follows the term ‘industry’ simply refers to any non-academical company or position.

After spending almost fifteen years of my life in various universities, going from a freshman student to a postdoctoral researcher in mathematics, I finally decided to take a big leap and move from the academical world to the private sector. The process of the transition was not completely simple, so I thought that it would be useful for me to write down some of my experiences. In particular, I aim to tell here the kinds of things that I would have liked to have known beforehand. In this text I’ll first say a few words of my professional background and then describe the transition process from preparation to finish.

Caveat lector: this is a description of a specific journey from the academical world to the private sector by this specific mathematician, not a step-by-step guide. In particular, when I was born I hit the birth lottery jackpot and I am in the top 1% of pretty much any unfair privilege group, YMMV.

Personal Background

I started my math studies at the University of Helsinki in 2006, and roughly ten years later I got my PhD in mathematics from the very same institution. Despite studying a small amount of computer science, university pedagogy and physics, by my estimate I finished as a ’95% pure mathematician’. By this I mean that even though I’ve always been interested in things beyond just mathematics, my research profile and thus majority of my work was completely focused in math for the sake of math in a field with few immediate applications to the real world.

After getting my PhD I spent four-ish years doing various postdocs at UCLA (3 months), University of Jyväskylä (6 months), the Charles University in Prague (1 year) and again at University of Jyväskylä (2 years). Getting the chance to work in so many different research environments was a huge plus and it considerably expanded both my research profile and my social networks, but it also had the downside of having to move around a lot during these years. The constant instability and uncertainty about future workplaces can be, and was for me, very grating. In the end the yearning for stability was one of the larger motivations for the transition, together with the ever increasing need to actually live in the same city as my wife, family and friends. Travel is much more fun when it’s the exception and not the rule.

During my graduate studies and my postdoc periods my work concentrated on research and teaching, but one of my primus motors in life is learning new (technical) things and I’ve pretty much always had the hobby of ‘studying various topics’. Usually these hobbies are short-lived, spending few months studying something new, but they do build up during the years. In particular, I’ve had an on-again, off-again type of relationship with programming since I was 16. I wouldn’t go as far as saying that I’m was good programmer when the process started a year ago, but I was an adequate script-writer in a few different languages.

Motivations for the change

Besides the ‘negative pressure’ from instability of the academical work life and the frustrations from the cumbersome application rounds, there were also several positive motivations to seek new professional vistas.

A particularly large influence on the decision to transition was hearing experiences of other people moving to the private sector. Especially in hindsight I get the feeling that mathematicians in the academical career path have a skewed view of the employment possibilities outside of the math department. I don’t think that it is intentional propaganda, but I believe that identifiable role models have a huge effect on what kind of life and career people pursue, and the role models available at math departments tend to be very biased. From the university research and teaching personnel with permanent positions that I personally know, I’d say one in a hundred have had significant work experience in the private sector after getting their PhD. The rest have, as far as I know, followed the unwavering path of academy positions until tenure. There is nothing bad in this career progression, but it would be healthy to be more aware of the alternatives. And yes, there are of course career events and colloquia where we get to hear from the other possibilities, but those don’t have nearly the same impact as spending countless hours in a community where 99% of the people you look up to have gone through the same path. I do not know how math-specific this bias is and it is probably related to the fact that research in pure mathematics is done only in universities — it would be interesting to plot the percentage of e.g. tenured professors in various department who have worked for at least 12 months in the private sector after receiving their PhD, but the data would take some time to come by.

The important lesson here for me was to find out that there is big world of interesting and challenging work opportunities outside the walls of the math department. Indeed, besides the second hand stories, I had the chance to do some professional consulting related to AI and mathematics and thus practice a bit what it is like in the industry. I was very pleasantly surprised to find complicated and interesting problems that required methods from my mental research toolbox to solve. The aims and goals can be, of course, a little less fanciful than ‘exquisite mathematical beauty’ and more in the vein of ‘the board requires a 5% performance increase this quarter’, but this doesn’t mean that the work isn’t fascinating. Furthermore, having quantifiable achievable goals can do wonders for your mental well-being. In particular, in my research I very rarely if ever feel that I’ve exceeded the expectations of others or of myself — the proof could always have been prettier or I could have found the correct lemma sooner — whereas producing a 18% speed increase in this quarter will get you appraisal and pats on the back, maybe even a bonus!

Within the private sector, I also feel that I can do more direct Good than in the research environment. This is not to say that research does not do Good — I strongly believe that fundamental research, knowledge for the sake of knowledge, is not only important but even crucial for humanity at large. However, the benefit of research in pure mathematics to the general human condition can be quite a few steps detached from the day-to-day life of a mathematician. And even though I believe the work to be useful it does not mean that I feel it in my heart of hearts on a daily basis. Working as a technical consultant isn’t quite the same as healing the sick, but at least you can imagine a chain of effects leading from your work to concretely helping the society.

For me, it has been eye-opening to see the different types of job opportunities the private sector has to offer for someone coming from the pure math research environment. And though you do sacrifice some freedoms the benefits can be very much worth it. This does not mean that the choice is easy or fast to make. For me the decision was both difficult and stressful. Especially since for pure mathematics it is exceedingly hard to apply for research positions if you spend a few years not publishing research articles in your field. For me the many long discussions with my wife about the topic were completely invaluable.

Addendum: This section has focused on the influences that were moving me to the private sector. This focus has the unfortunate effect of underrepresenting the various motivations I had to not leave the academia, and there are many of those. I won’t start listing all the best things in the academical world in here, but it simply can’t go unsaid that the biggest reason to hesitate leaving the academia was the people. Mathematics is absolute and without adjectives, but the mathematicians are anything but. The communities they form and which I’ve have had the privilege of being part of have given me experiences, friends and memories that I’ll treasure forever.

The transition

Even though the timeline of the situation was not quite that clear cut, for the sake of clarity of the exposition we’ll look at the progress in three steps: Preparation, Application submissions and Interviews.

Preparation

The idea of working in the private sector had been rolling in my mind every now and then, but I seriously started to consider it in May 2019. (Incidentally, the results and feedback of the Finnish Academy grant application rounds in math are usually announced around May.) I decided to steer my work and hobbies to a direction that would be more applicable not only to my current research and teaching but also to possible future non-academical jobs. I was still planning to possibly stay in academia, but I started hedging my bets.

The first thing to do was trying to figure out what kind of jobs I could be interested in and what was available. To this end LinkedIn and some other local job-seeking sites proved to be very helpful, along with friends who were already working in the industry. In the end it turned out that jobs related to AI, cybersecurity or scientific programming were those to most arouse my interested and the common denominator in all these positions was programming. Thus the next step was to enhance the skills to an more employable level.

Though I didn’t need to learn to code from scratch, it didn’t mean that I could turn into a proficient programmer overnight, so the plan was to figure out ways to include some programming as a part of my daily routines and maybe start a few hobby projects as well. After some discussions with people already in the private sector, I also set up a proper GitHub account and uploaded any reasonable coding projects I had had in the past. Think of GitHub as an extension of your CV and remember that, if you are like me and don’t have a lot of things to showcase, it is better to be able to signal both interest and that you are able to design and implement algorithms in readable commented code than to have nothing to show. Depending on your level of coding skills, I would also recommend looking at various online courses available. There is a large variation in their price, quality and value, but for example the deep learning specialization course by Andrew Ng at Coursera was great for me both in refreshing my Python skills and in solidifying my scattered knowledge concerning neural networks in practice.

Having even a minimal presence at job sites can be very fruitful since, as it turns out, there are people out there looking for math PhDs who know how to program. I had thought that it would take me a long time to make myself hireable and that I would need to have credentials X, Y and Z before starting to seriously apply for positions. In removing this misunderstanding I was helped along by a headhunter who cold-called me in December to ask if I have been planning to work at the private sector. It turns out that there is demand in the industry for people who have a PhD and know how to write code. In the end it got the feeling that many companies seemed to be more interested with the fact that I’m the kind of person who will learn to be better at given tasks than with the particular technical skills I currently possess.

Application submissions

My original plan had been to wait until around June to start applying for positions with my certification-boosted CV, but this changed with the call from the aforementioned headhunter. In my limited experience, headhunters tend to be kinda hype-y about your hireability and skills, but the pep-talks I got from them were really useful for me and I decided to give a go at applying for a position in a company that we will call Company D. Unrelated to this, on the same week a colleague sent me an email about an interesting math consulting position they had noticed, and motivated by the push from the headhunter I decided to give it a go and apply for this Company S as well. The key point I got from the headhunter and what you should remember is that your skills as a PhD are valuable and there are companies who would be eager to have you.

To apply, you then of course need a CV. Most people know that you should adjust your CV for each position you are applying for, but even further I highly recommend to also create a new CV from scratch if you haven’t applied to private sector before. This is due to the fact that most academical CVs I’ve seen, at least for mathematicians, tend to be several pages long and contain a lot of specifics. (See below.)

Figure: For comparison, here are side by side page 2/4 of my ‘academical CV’ (https://luisto.fi/documents/CV-Luisto.pdf) and my one-page ‘industry CV’ (https://luisto.fi/documents/CV-Luisto-OnePage.pdf).

Figure: For comparison, here are side by side page 2/4 of my ‘academical CV’ (https://luisto.fi/documents/CV-Luisto.pdf) and my one-page ‘industry CV’ (https://luisto.fi/documents/CV-Luisto-OnePage.pdf).

The kind of detailed information in an academical CV is often relevant when applying for academical positions where the panel might want to check for specific experiences or merits, but usually a complete overkill for a more normal recruitment process. Google around for examples of modern CVs and read a few blog-posts on LinkedIn on what the people who read the CVs have to say about the topic. Make it easy for the reader to quickly see why they should be interested in you and ask you for an interview.

One very important piece of advice from the headhunter was, that companies can be very interested in your communication skills. (This might be particularly true for people with science PhDs as there are some not completely inaccurate stereotypes about our communication abilities.) In this it can be very useful to highlight your teaching experience, public outreach activities and any presentations you have given. You don’t need to be a superb orator, but it is good to signal that you can discuss complicated topics with people who are not in your own small research group bubble. Most of the jobs require you working as a part of a team, and teams tend to work bad if the information is not flowing. Communication skills can and should be signaled in your CV, but bear in mind that this is something that the recruiters will be assessing also in the interviews.

I’ll go into more detail about the interview process in the next section, but the end result here was that I wasn’t hired by either of the two companies D or S. Both companies did say, however, that they would like to contact me in roughly six months in their next hiring round, and claimed that I had apparently been ‘the best of the ones not hired’. At this point I decided to wait until June for most of applications, but to take action if anything particularly interesting came up. Thus I ended up sending an application to the company that ended up hiring me after a good friend mentioned that they are looking for an AI-expert / Data Scientist. Around the same time I was also contacted by Company E who had seen my CV on a job-seeking site and asked me for a few interviews. With Company E I feel that the interviews went well and I probably would have gotten an offer from them had the COVID-19 shutdown not started during the interview process.

Interviews

Academical positions, at least on the postdoc level, very rarely have actual job interviews. Thus, by December 2019 I had had essentially one proper job interview for a university teacher position, but no relevant interview experience for technical roles in the private sector. Even though I am quite extroverted and happy to improvise, I was exceedingly nervous. Here there is another good argument for starting to apply early as you will get experience in being in interviews. I don’t know if I learned to be interviewed better, but at least after the first few times I was a lot less nervous before and during.

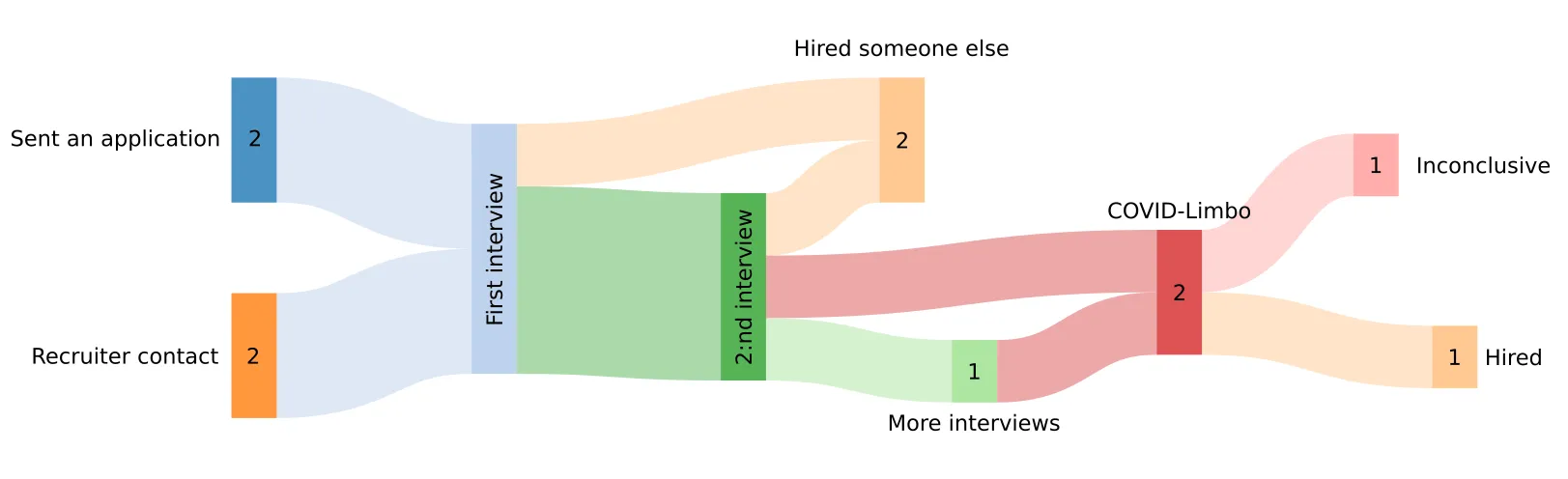

The diagram below tries to visualize the flow of the interviews for the four companies I ended up applying to. In short; in one company I had only one interview, in the other companies I got to second interview as well and for the company that in the end hired me I had three interviews all together. The interviews varied a lot from company to company, but in those with multiple interviews the first one tended to be a more high-level discussion with some people from HR, and the latter interviews had more people from the actual teams that I would be working with.

Figure: Because literally everything is better with Sankey diagrams, and because it’s nice to have some colorful pictures every now and then.

Figure: Because literally everything is better with Sankey diagrams, and because it’s nice to have some colorful pictures every now and then.

No two interviews were alike, which is quite natural since no two discussions are alike. Remember; you are at the interview because they are interested. You are a valuable asset and you are there to discuss if you are the best fit for each other. The interview is not an exam but a first date where you are talking about each other’s preferences to see if your skills and interests are a match. Don’t just answer questions, but try to ask questions yourself as well to see if the company and team feel like the right place for you. They are not looking for an automaton who’ll complete tasks but a colleague to work with.

In all interviews I was asked to introduce myself and ‘tell about yourself’. In the first interviews I think I was a bit too eager, telling a lot more than needed for the position, in later interviews I decided to give somewhat more broader strokes. Like with the CV, the ‘tell about yourself’ is good to fine-tune to the particular company and position. Even better if you are able to read the room — try to feel what information is interesting to the particular people you are talking with. The same holds true for many other topics that will come up; try to figure out both beforehand and in situ how your skills and experiences could be useful for the particular position.

The topic of ‘communicating and working in groups’ also came up in various forms, and here it’s good to remember that they are not asking you to list credentials on how you are good at communicating and working with others, but you need to communicate the information to them. The whole interview is you working together with this group of people, trying to solve to question of how well you would fit together. In one company, part of the process was also giving me a technical AI-paper and asked to give a short presentation about the content to the team I would be working with. This was, naturally, a bit scary but also a big plus as it helped me to imagine what it would be like to work with these people.

Naturally, I’ve omitted here many of the standard interviewing advice like ‘dress sharply’ and ‘research the company beforehand’ as I’ve wanted to focus on the things that I feel were specific to me being a math PhD applying for the first time to the private sector. Some of the general advice is obvious, some of it not and I do recommend Google and reading a few blog posts about what interviews are all about.

In a nutshell: Knowing at least one programming language is a huge plus, you should flaunt your teaching experiences as communication skills, and understand that you are a valuable asset that many companies are happy to hire.

Afterword

A year ago when I was first starting to seriously consider leaving the academia, the idea filled me with varying levels of dread. I had many conflicting fears and worries, many of them revolving around feelings of loss and defeat. Now, a year later, I don’t feel at all like I had given up or lost. There are some wistful feelings, of course, but mostly I feel relief, content and excitement. My exciting job will actually stop in the afternoons, I get to sleep in my own bed next to my wife every night of the week and I don’t have to spend a month every year just to apply for my own job. The decision was hard and stressful and it took me months to process and to come to terms with, but in the end it was worth it. So if you are planning a transition and feel worried: it’s quite normal to be scared, take it easy, talk to your loved ones about it and be assured that it can actually feel pretty awesome on the other side.

This text has described the transition phase of moving from academy to the industry. I am planning to write two more longer texts, one in roughly three months from now and another roughly one or two years from now, describing what happens after the transition. At least if there seems to be interest to such texts. And if I remember to.

What I personally look forward to in these future texts will be the story of what happens with my relationship to mathematical research. I currently think that there will be little hope for me to continue to produce cutting-edge new math, at least by myself, but I’d be ready to believe that I could be able and willing to make contributions to some collaborative projects where the onus of the work is not on me. Even more than such projects that do aim to produce publishable results, I hope that toying around with a few choice research problems that I haven’t quite cracked yet will remain a part-time hobby. But I guess only time will tell. Thank you for reading.